05 June 2012

In Ancient Egypt, the river Nile created a simple divide of east and west, life and death. To the east the sun rises: life, before dying as it sets in the west.

As a result, despite there being temples located on the east and west shore of the Nile, the purpose of these temples is clearly divided into temples for the living and temples relating to death.

The temple constructed by Hatshepsut, the female Pharaoh is located on the west shore and so it is designated the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut.

Hatshepsut is an interesting character. She was the daughter of Thutmose I, wife of her half-brother Thutmose II, and stepmother/regent/co-ruler of Thutmose III. As Thutmose III was too young to succeed when his father died, Hatshepsut acted a regent. However instead of handing the throne over to her stepson when he came of age, instead she declared herself Pharaoh and put him in charge of her army. It has been argued that this allowed Thutmose III to focus on his military prowess and skill to transform Egypt into an empire when the chance arose. Thutmose III never displayed any animosity to Hatshepsut's position during her reign; he never led an uprising against her despite the resources and skills at his disposal.

The complex actually has some substantial size to it, but because of the layout, and being dwarfed by the whopping great cliffs behind it, it manages to look rather small and compact.

Another feature which designates this temple a mortuary temple are the gigantic statues of Hatshepsut in the mummified attire usually associated with Osiris, god of the dead and afterlife.

Statues of Hatshepsut are intriguing in that they depict her as either a female or a male, depending on the function of the statue. In more formal pieces she is presented with all the trappings of a Pharaoh including the false beard, and carrying the necessary symbols of office. Even her breasts and feminine features have been removed, providing an altogether more masculine appearance.

In the less formal pieces she is depicted as a woman, wearing attire in line with that worn by aristocratic women of the time. It is believed more likely that this is how she presented herself at court and that she never wore the masculine Pharaonic attire in which she has been depicted.

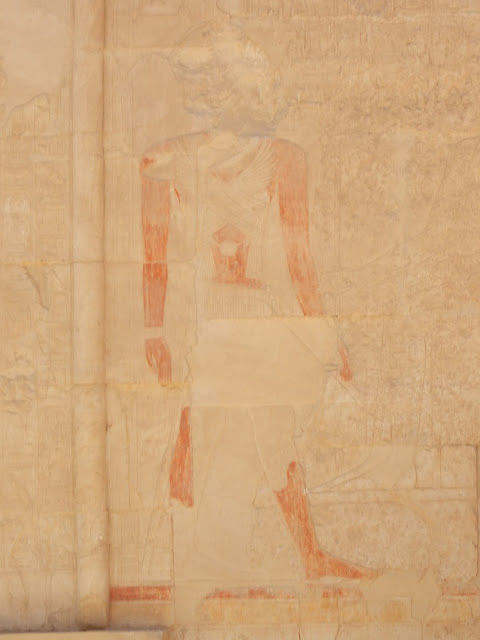

I mentioned that Hatshepsut's stepson Thutmose III had a few issues with his stepmother. These don't appear to date from during her lifetime, but only the later years of his subsequent reign. It was during this time that a number of the more obvious depictions of Hatsephsut as a Pharaoh (instead of as a queen) were desecrated. Her features were harshly removed from friezes, her cartouche rubbed out or replaced completely...

Scholars and Archaeologists have hypothesised that by then all of Hatshepsut's valued advisors were dead and so couldn't stop Thutmose III, and that his motive was to restore Hatshepsut to a more 'female' position. However, given we're discussing events that took place 3000 years ago, I'm not sure we should so easily assume that he simply wanted to relegate her to a lower position more aligned with the roles traditionally held by women.

As historians cannot even accurately date her reign, there are obviously huge chunks of her history missing from our current records. What we do have are more likely to be major achievements and milestones that are being celebrated through these monuments, paintings and statuary.

In addition to cementing Hatshepsut's origins as the child of a god (Amun-Ra in this instance); something all Pharaohs seem to have done, this temple also documents and celebrates the impressive trading expedition Hatshepsut launched to the land of Punt.

Though the exact location of Punt is still being debated by historians, it was most likely south-east of Egypt, around the Horn of Africa and possibly, the southern Arabian Peninsula. If it was located around the Horn of Africa, it may be that it was ideally placed to act as a trading hub for goods coming from southern Africa and parts of the Arabian Peninsula and travelling up the Red Sea towards the Mediterranean.

What is known is that it exported (and possibly produced) gold, aromatic resins like Frankincense and Myrrh, blackwood, ebony, ivory, and wild animals (giraffes, hippopotami, leopards).

Documented on the walls of the temple, the Egyptian expedition brought back all of these, including Frankincense and Myrrh trees to plant on the temple's terraces.

*The photos below don't depict the Punt expedition, but instead other sections of the temple walls.

Incorporated into the temple structure is also a smaller temple dedicated to Hathor. This temple's columns are decorated with the features of the goddess (including her cow ears).

In Ancient Egypt, the river Nile created a simple divide of east and west, life and death. To the east the sun rises: life, before dying as it sets in the west.

As a result, despite there being temples located on the east and west shore of the Nile, the purpose of these temples is clearly divided into temples for the living and temples relating to death.

The temple constructed by Hatshepsut, the female Pharaoh is located on the west shore and so it is designated the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut.

Hatshepsut is an interesting character. She was the daughter of Thutmose I, wife of her half-brother Thutmose II, and stepmother/regent/co-ruler of Thutmose III. As Thutmose III was too young to succeed when his father died, Hatshepsut acted a regent. However instead of handing the throne over to her stepson when he came of age, instead she declared herself Pharaoh and put him in charge of her army. It has been argued that this allowed Thutmose III to focus on his military prowess and skill to transform Egypt into an empire when the chance arose. Thutmose III never displayed any animosity to Hatshepsut's position during her reign; he never led an uprising against her despite the resources and skills at his disposal.

The complex actually has some substantial size to it, but because of the layout, and being dwarfed by the whopping great cliffs behind it, it manages to look rather small and compact.

Another feature which designates this temple a mortuary temple are the gigantic statues of Hatshepsut in the mummified attire usually associated with Osiris, god of the dead and afterlife.

In the less formal pieces she is depicted as a woman, wearing attire in line with that worn by aristocratic women of the time. It is believed more likely that this is how she presented herself at court and that she never wore the masculine Pharaonic attire in which she has been depicted.

Scholars and Archaeologists have hypothesised that by then all of Hatshepsut's valued advisors were dead and so couldn't stop Thutmose III, and that his motive was to restore Hatshepsut to a more 'female' position. However, given we're discussing events that took place 3000 years ago, I'm not sure we should so easily assume that he simply wanted to relegate her to a lower position more aligned with the roles traditionally held by women.

As historians cannot even accurately date her reign, there are obviously huge chunks of her history missing from our current records. What we do have are more likely to be major achievements and milestones that are being celebrated through these monuments, paintings and statuary.

In addition to cementing Hatshepsut's origins as the child of a god (Amun-Ra in this instance); something all Pharaohs seem to have done, this temple also documents and celebrates the impressive trading expedition Hatshepsut launched to the land of Punt.

Though the exact location of Punt is still being debated by historians, it was most likely south-east of Egypt, around the Horn of Africa and possibly, the southern Arabian Peninsula. If it was located around the Horn of Africa, it may be that it was ideally placed to act as a trading hub for goods coming from southern Africa and parts of the Arabian Peninsula and travelling up the Red Sea towards the Mediterranean.

What is known is that it exported (and possibly produced) gold, aromatic resins like Frankincense and Myrrh, blackwood, ebony, ivory, and wild animals (giraffes, hippopotami, leopards).

Documented on the walls of the temple, the Egyptian expedition brought back all of these, including Frankincense and Myrrh trees to plant on the temple's terraces.

*The photos below don't depict the Punt expedition, but instead other sections of the temple walls.

When she became Pharaoh, Hatshepsut began using her father's titles as opposed to the ones usually assigned to the Queen. Of these titles, The Strong Bull of his Mother was the one of the few she didn't take. The reason is that she didn't need to define herself as the son of the goddesses Hathor and Isis because instead she could align herself with the goddesses themselves.

Indeed, the imagery of Hathor, who is often depicted as a cow, is visible throughout the site and the valley in which the temple is located was seen as sacred to the goddess Hathor at that time.

Incorporated into the temple structure is also a smaller temple dedicated to Hathor. This temple's columns are decorated with the features of the goddess (including her cow ears).

These photos don't half do the place justice, and I'll admit, it's still on my bucket list to return to.

No comments:

Post a Comment